The history of the Gergovia plateau

Following the Gergovia Plateau footpaths means immersing yourself in the 52 BC battle between Vercingetorix and Julius Caesar, which was a decisive event in the Gallic War. It is also an opportunity to explore the history of the Arverni, the influential Gallic tribe that made Gergovia their capital.

The famous Battle of Gergovia

Julius Caesar’s first military defeat

Here, facing the capital of the Arverni, the relentless forward drive of the Roman war machine finally ground to a halt. Since 58 BC, Caesar’s legions had been celebrating one victory after another. Now, in the spring of 52, its fortunes changed; despite its methodically conducted siege work, the Roman army found itself marking time. The exceptional quality of Gallic defence works, the advantageous position of the oppidum and the vigorous resistance by the defenders all combined to push back the assault led by Caesar.

The Roman army needed to launch an onslaught that would be both brief and brutal in order to protect its own soldiers. The outcome of the battle was sealed in less than a single day. Of the thousands of combatants involved in the Battle of Gergovia, Caesar admitted to only a few hundred victims. Enough, however, to force him to raise the camp.

A strategic battle

For both forces, the duration of a siege is an important factor that can hand the victory to either side. With every passing day, troops face dwindling supplies, surprise attacks, marches, and betrayals. The first few weeks of a siege are vital to strengthening and extending troop positions, establishing strategy, and upholding the morale of regular and auxiliary soldiers.

The account of the battle according to Julius Caesar

The Gallic War is one of the best-known conflicts of ancient times, recounted in a series of eight books authored by Julius Caesar and one of his lieutenants, Hirtius. This written episode is the only actual description that exists of these long-ago events. In the seventh book of his war diary, De Bello Gallico, Caesar gives a detailed account of the military campaign waged against the peoples of central Gaul in 52 BC, in particular the siege of Gergovia. It should be remembered that what is presented here is Caesar’s own personal account, the only one available to us – but that archaeology is seeking to provide a more nuanced picture of the event.

The sequence of events during the battle

Caesar’s army against Vercingetorix’s troops

In 52 BC, Vercingetorix leads the Gallic rebellion against Julius Caesar, who has already seized several Gallic territories. The young Arverni leader lures Caesar and his 6 legions (36000 men) to his native land of Gergovia. The Gallic troops are much more numerous and are positioned on the southern slopes of the oppidum (Gallic fortified town) and on the nearby hills to the south and west.

Caesar sets his Main Camp in the plain to the southwest of the Gallic town. At night, he takes over one of the Gallic camps on the La Roche-Blanche hill, where he sets his Small Camp. He connects his two camps with a double-ditch and palisades with protect the Roman army’s movements.

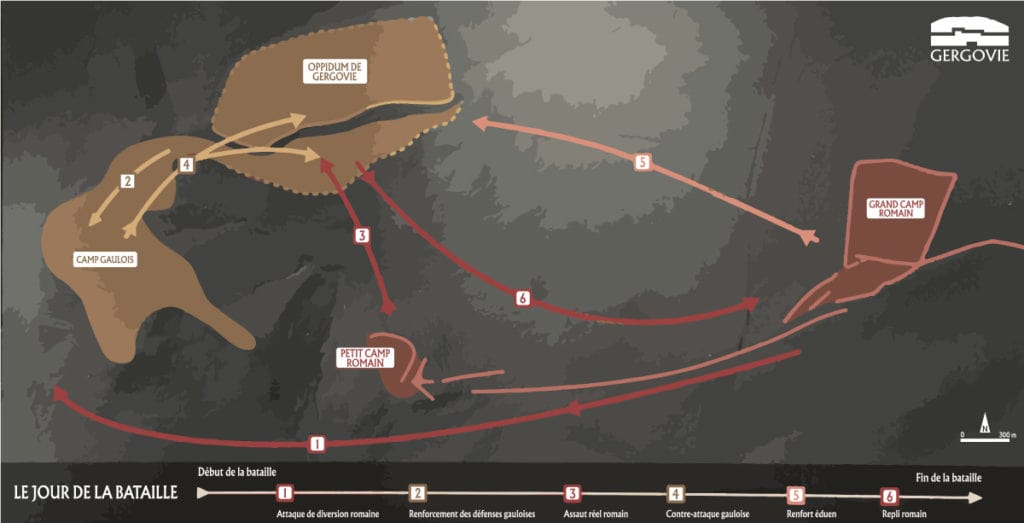

The day of the battle according to Caesar

1 – The diversionary attack by Roman troops

“In the middle of the night, Caesar sends several troops of horse; he orders them to range in every quarter with more tumult than usual. At dawn he orders a large quantity of baggage to be drawn out of the camp, and the muleteers with helmets, in the appearance and guise of horsemen, to ride round the hills. To these he adds a few cavalry, with instructions to range more widely to make a show. From Gergovia, which overlooks the Roman camp, these troop movements are clearly visible to the Gauls, but they are too far away to be able to distinguish the details.”

2 – The strengthening of the Gallic defences

“The suspicion of the Gauls are increased, and all their forces are marched to the western side of the oppidum to defend it.”

3 – The actual Roman attack

“Caesar, having perceived the camp of the enemy deserted, covers the military insignia of his men, conceals the standards, and transfers his soldiers in small bodies from the greater to the less camp, and points out to the lieutenants whom he had placed in command over the respective legions, what he should wish to be done; he sets before them what disadvantages the unfavorable nature of the ground carries with it.

The town wall was 1200 paces distant from the plain and foot of the ascent, in a straight line, if no gap intervened; whatever circuit was added to this ascent, to make the hill easy, increased the length of the route. But almost in the middle of the hill, the Gauls had previously built a wall six feet high, made of large stones, and extending in length as far as the nature of the ground permitted, as a barrier to retard the advance of our men. The soldiers, on the signal being given, quickly advance to this fortification, and passing over it, make themselves masters of the separate camps.

Caesar, having accomplished the object which he had in view, ordered the signal to be sounded for a retreat; and the soldiers of the tenth legion, by which he was then accompanied, halted. But the soldiers of the other legions, not hearing the sound of the trumpet, because there was a very large valley between them, were however kept back by the tribunes of the soldiers and the lieutenants, according to Caesar’s orders; but the soldiers continued to advance until they reach the foot of the town’s fortified ramparts and gates.”

4 – The counterattack by the Gauls

“In the In the mean time those who had gone to the other part of the town to defend it at first, aroused by hearing the shouts, and, afterward, by frequent accounts, that the town was in possession of the Romans, sent forward their cavalry, and hastened in larger numbers to that quarter. As each first came he stood beneath the wall, and increased the number of his countrymen engaged in action. Neither in position nor in numbers was the contest an equal one to the Romans; at the same time, being exhausted by running and the long continuation of the fight, they could not easily withstand fresh and vigorous troops.”

5 – The Aedui reinforcements

“While the fight was going on most vigorously, hand to hand, and the enemy depended on their position and numbers, our men on their bravery, the Aedui (allies of the Romans, who had promised reinforcements of some 10,000 men) suddenly appeared on our exposed flank, as Caesar had sent them by another ascent on the right, for the sake of creating a diversion. These, from the similarity of their arms, greatly terrified our men; and although they were discovered to have their right shoulders bare, which was usually the sign of those reduced to peace, yet the soldiers suspected that this very thing was done by the enemy to deceive them. Our soldiers, being hard pressed on every side, were dislodged from their position.”

6 – The Roman withdrawal

“The tenth legion, in a slightly better position, blocks the counterattack by the Gauls, who are over eager in their. The tenth legion, which had been posted in reserve on ground a little more level, checked the Gauls in their eager pursuit. The legions, as soon as they reached the plain, halted and faced the enemy. Vercingetorix led back his men from the part of the hill within the fortifications.”

The aftermath of the siege of Gergovia

At the end of the siege of Gergovia, Caesar admitted to having lost 700 men and 46 centurions and, unable to relaunch an attack, abandoned the battlefield and broke camp two days later.

Following his victory, Vercingetorix rallied the support of new allies, in particular the Aedui, up till then a long-standing partner of Rome. Shortly after the battle of Gergovia and despite a certain reluctance, the Aedui, who lived in the area now known as Burgundy, agreed to Vercingetorix being appointed supreme commander of the fight against the Romans at Bibracte, the stronghold of the Aedui.

Now in command of the Gallic revolt, Vercingetorix resumed his scorched-earth tactics, harassing the Roman army as it made its way towards Rome’s provinces. Despite these successes, he was eventually routed by his enemies, who were strengthened by the arrival of Germanic cavalry, and decided to retreat to Alesia. Caesar seized the opportunity to surround and lay siege to the Alesia oppidum. Despite their numerical superiority, the Gallic troops were decisively pushed back and defeated after almost two months under siege. The Roman fortifications, the superior organisation of the Roman troops and Caesar’s winning strategy eventually toppled the Arverni leader who chose to surrender to spare his men.

Despite this surrender, however, the Roman general faced continuing opposition from new Gallic coalitions. It was not until his victory at the siege of Uxellodunum (in the region of present-day Cahors) that Julius Caesar finally completed his conquest of Gaul.